Diarrhoea in Young Pigs

Overview

Diarrhoea is one of the most common and important diseases in piglets. Among the most frequent causes of diarrhoea in piglets in Ireland are Escherichia coli (E. coli), rotavirus, clostridial bacteria, Isospora spp. (coccidiosis), Enterococcus durans , Salmonella typhimurium and Lawsonia Intracellularis . E.coli is the most common bacterial cause of diarrhoea in piglets.

There are many different strains of E.coli bacteria. The organism usually resides in the intestines of pigs and other animals, without causing disease. Protection occurs in piglets from the antibodies that are present in sows’ colostrum and milk. These are absorbed into the mucous lining of the intestine and inhibit bacterial and viral attachment. If piglets do not receive enough colostrum or if the colostrum is not sufficiently enriched with the appropriate antibodies, piglets commonly succumb to E. coli diarrhoea around 5 days of age. However, there are further risk periods between 7 and 14 days and again at weaning.

Following weaning, E. coli can now attach to the intestinal wall, causing inflammation (enteritis) and allowing fluid loss into the intestinal tract resulting in profuse watery diarrhoea.

Piglet mortality from diarrhoea should be less than 0.5%. In severe outbreaks of E. coliv diarrhoea, mortality can rise to over 7%.

Clostridium perfringens is also commonly associated with diarrhoea in piglets. There are several strains of Clostridium perfringens. These can produce anything from a low grade diarrhoea at any stage up to weaning, to a peracute haemorrhagic enteritis, which commonly kills before diarrhoea is seen, often in the first 24 to 48 hours of life.

Coccidiosis is commonly found in piglets from 7 to 14 days of age. Rotavirus diarrhoea usually appears in waves in individual litters or groups of litters in the same farrowing house and is most common in the second half of lactation. Outbreaks of acute diarrhoea and high mortality may suggest porcine epidemic diarrhoea or transmissible gastro-enteritis caused by coronavirus but these diseases are not currently diagnosed in Ireland.

Clinical Signs

Clinical signs depend on the type of diarrhoea involved, the age of piglets and whether the diarrhoea is acute or chronic.

In acute disease, the following signs become apparent:

- Dead piglets (previously seen healthy)

- Area around the rectum and tail is wet

- Watery, yellowish diarrhoea

- Piglets huddled together shivering

- Vomiting

As the diarrhoea progresses piglets become dehydrated, their eyes become sunken and their skin appears leathery. Before death, piglets may be found on their side vomiting.

In chronic cases, signs include:

- Mortality that is generally lower and the clinical signs less aggressive

- Disease that is more common in 7 to 14 day old piglets

- Yellow or white coloured diarrhoea

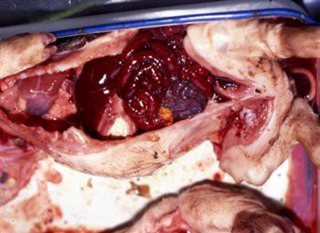

Clostridium perfringens type C associated diarrhoea

Piglets mainly from 1 to 3 days are most at risk. Clinical signs include sudden onset of haemorrhagic diarrhoea followed by collapse. Death is common.

In less acute cases brownish liquid faeces are commonly seen at 3 to 5 days of age. In rare cases, piglets develop persistent, pasty, grey diarrhoea and become progressively emaciated.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of diarrhoea can be carried out by:

- Clinical examination

- Submission of a rectal swab or faecal sample from a recently dead or living pig. This sample may be analysed using culture or PCR for detection of bacteria.

- Using litmus paper. This can distinguish if the diarrhoea is alkaline or acid pH. As E. coli diarrhoea is alkaline, the paper changes to blue colour, whereas with viral infections, that are generally acidic, the colour changes to red.

- Post mortem examination – A fresh carcase should be submitted as soon as possible after death. Clostridial bacteria can be quite difficult to diagnose so early submission of samples to the laboratory is important.

Treatment

E. coli diarrhoea is often responsive to injectable antibiotics e.g. amoxicillin, ampicillin fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins and potentiated sulphonamides.

In extreme outbreaks of E. coli, sows feed can be top dressed with the prescribed antibiotic, following entry to the farrowing house for up to 14 days. This can be effective in reducing the shedding of harmful bacteria in the faeces.

Oral administration of zinc oxide to the sows has been reported to reduce incidence and severity of E. coli diarrhoea in piglets.

Treatment of pigs with clinical signs of Clostridium perfringens type C will have minimal gains as lesions are usually irreversible at the onset of diarrhoea.

Other treatment options:

- Provide electrolytes to sick pigs to prevent dehydration

- Install heat lamp as a source of additional heat

- Use wood shavings or paper clippings in the pen

Assess the response to treatment of medicine. If there is no change after 12 hours, consider changing medicines

Control

- Strict adherence to ‘all-in, all-out’ pig flow

- Install foot dips between farrowing rooms

- Clean and disinfect the farrowing rooms after every batch

- No cross-fostering between litters during an outbreak

- Ensure all piglets get adequate levels of colostrum

- In large litters adopt the practice of split suckling

Immunisation by vaccination is obviously the best and easiest way to protect piglets against diarrhoea in the first days of life. Vaccines are available to protect against E.coli strains that contain the following antigens F4ab (K88ab), F4ac (K88ac), F5 (K99) or F6 (987P) and Clostridium perfringens type C. The vaccine is administered to the sow in late pregnancy. It is important to ensure that a primary course of two doses is completed in adequate time prior to parturition and that piglets are observed carefully to ensure they receive adequate colostrum – especially where mis-mothering can happen with gilts / young sows. Sows must receive a single dose 2-4 weeks prior to each subsequent farrowing